Ever since my parents gave me a camera for my twelfth birthday, I have almost never left home without one. I love the weight of the camera in my hands, the sound and the feel of a shutter as it clicks, and the idea that one can preserve memories and moments in time. A photograph can capture sadness, pain and suffering, or it can capture joy, excitement and love – and every possible thing in between. Photography brings me back to that very moment in time in which a picture was taken. When I look at a photograph, I can again feel the sun on my skin as I walked outdoors, smell the incense floating through a busy marketplace, or hear the laughter of a group of children as they play outside.

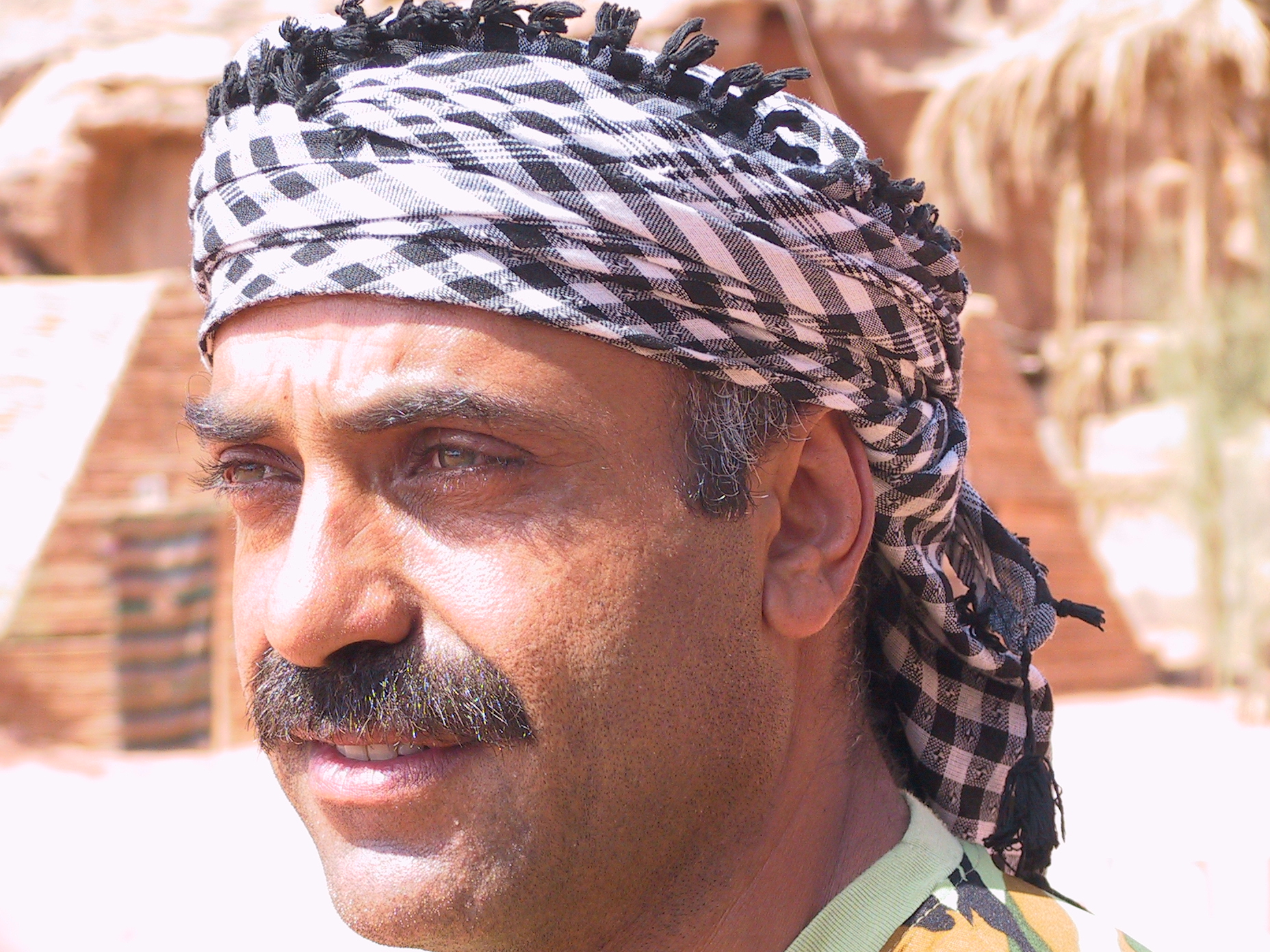

When I moved to Jordan to become a Peace Corps volunteer, I found that taking photographs was much more difficult compared to other places in which I had traveled, due to the country’s inherently conservative society. Taking pictures of women was considered taboo; taking pictures of men made people think you were a spy. In very rural areas, people believed that having your picture taken meant that a piece of your soul would be taken as well.

Thankfully, over time – and due to the nature of the Peace Corps – I slowly became a part of my local community. As people began to accept me - and get used to seeing me lugging around a huge camera wherever I went – they began to open up to me, and to the idea of having their photographs taken. And the more I became one of them, as I learned their language and their culture, the more comfortable I became asking people if I could photograph the more intimate moments of their lives.

At a time when the Israeli-Palestinian conflict was going on to Jordan’s west, the Iraq war to the east, and the Lebanese-Israeli war to the northwest, I found that photography not only helped me to preserve treasured and valuable memories for myself, but also helped me to convey scenes of normalcy to my friends and family back home. In a region seemingly constantly marred by conflict, photography helped me demonstrate a side of life in the Middle East that many Americans don’t see –a life that is, in most respects, just like ours.

-Vanessa de Bruyn is a Foreign Service Officer and a returned Peace Corps volunteer. She served in Jordan as a TEFL volunteer from 2005-2007. In addition to Jordan, she has lived in the West Bank, China, Yemen and Portugal and has traveled to – and taken pictures in – over 30 other countries.